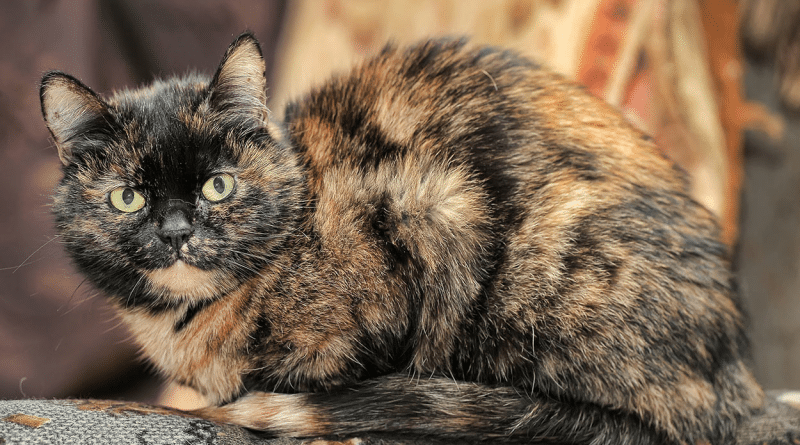

Introduction to Genetics, Case Study 1: Tortoiseshell cat colour

Are you female? If so, you are a mosaic of X chromosomes! Learn how tortoiseshell cats reveal the fascinating phenomenon of X-inactivation.

Previously in this series: Introduction to Genetics 6: Inheritance and variation

Genes and genetic mechanisms produce organisms in complex and subtle ways, and it isn’t always easy to glance at an animal and see this complexity for yourself. But tortoiseshell cats allow us to do exactly that!

We discussed in a previous article that mammals have two copies of each chromosome aside from the sex chromosome. Because females have two copies of the X chromosome, whereas males only have one, you would expect females to produce twice as many X-chromosome gene products as males. To avoid this situation mammals evolved something called ‘X-inactivation’. This involves ‘switching off’ one of the female’s X chromosomes. The key part is that (in humans and cats) this inactivation is done at random, and at an early point in the developmental process.

We haven’t covered the developmental process in this series (because it is an immensely complex subject area in its own right!) but we will cover a little now. Mammals start off as a single cell called a zygote – this is the cell that results when a female’s egg cell is fertilised by a male’s sperm cell. The zygote contains the complete library of genetic information for that organism – half of it from the male parent and half from the female parent. The zygote will start growing by making copies of its genetic information and then dividing so that each new cell will also contain a copy of the complete genome for that organism.

Fairly early in the development of a female the cells ‘switch off’ one of their X chromosomes in a fairly random way. So if you have 100 cells when X-inactivation happens, afterwards you will have ~50 cells with only the maternal X chromosome active, and ~50 cells with only the paternal X chromosome active. Crucially this X-inactivation stays the same when these cells divide.

This means that if you are a female you are actually a ‘mosaic’ of different cells. Some of your body will be using your father’s X chromosome, and some of your body will be using your mother’s X chromosome. (If this idea sounds strange to you then make sure you also read about chimerism!) Most of the time this isn’t noticeable, but in tortoiseshell cats it is right there for everyone to see! A tortoiseshell cat has inherited different colour alleles from their parents: she may have a red allele from her father and a non-red allele from her mother. After X-inactivation, this means that some of her cells will produce red pigment, and some will produce black.

You might think that this would result in a uniform mixing of red and black hairs, but (as ever!) the situation is a bit more complicated than that. During development cells will start specialising according to the role they will end up playing. For example, 10 cells may specialise to be melanocytes (a kind of cell that produces pigment). They will move towards the outer layer of the organism, and start dividing again. If X-inactivation happens during this process then the cat will end up with 10 patches of colour, 5 red and 5 black, each of them derived from those initial cells.

Developmental processes are influenced by environmental factors and other genes, so the final coat colour will depend on exactly when X-inactivation happens, exactly how far each cell has to move, and hundreds of other factors. This means that, even in genetically identical twins (or clones), coat colour may be radically different! This is an excellent illustration of why trying to decide whether something is ‘genetic’ or ‘environmental’ is such a fruitless activity: every organism is a unique product of their genes and their environment.

The same mechanism is also responsible for the colouring of calico cats, with the difference that calico cats also have genes that create white spotting. So next time you see a tortoiseshell or calico cat take a closer look – you are seeing the direct result of X-inactivation!

Bonus thought: Is it possible to have a male tortoiseshell? You may think that because a tortoiseshell coat can only happen when a cat has two X chromosomes, and only females have two X chromosomes, that male tortoiseshells are impossible. And you would be almost right! However there are rare cases where a cat is born with three sex chromosomes – two Xs and one Y (usually due to a sperm or egg cell that was created with two sex chromosomes). This cat would be technically male (because being male is basically determined by having a Y chromosome) but would also have two X chromosomes, which undergo X-inactivation in the same way as in a female cat, resulting in a male tortoiseshell cat.

Having two Xs and a Y chromosome has other impacts as well. The resulting set of symptoms in humans is called Klinefelter syndrome. It usually causes infertility and occurs in approximately 1 in 1000 male births.

Next in this series: Introduction to Genetics, Case Study 2: Lethal white and frame overo