Can we prevent trigger stacking?

We can’t control everything – but are there ways that we can help prepare our horse to stay calm under pressure and be less affected by the unexpected?

No matter how hard we try to control the environment in which we interact with our horse, some things are always going to be outside our control. This makes trigger stacking something most of us will have to take into account at some stage. By preparing ourselves and our horse to deal with stress, we can reduce the chances of a bad reaction.

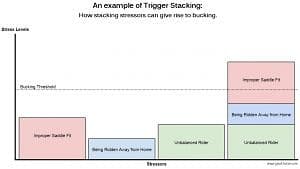

In a previous article we saw how trigger stacking can result in many little things adding up to cause a big reaction. One example would be several smaller stressors such as a poorly fitting saddle, unbalanced rider and being ridden away from home all coming together to cause a horse to start bucking. Taken individually, none of these stressors would produce this kind of reaction. But taken together, they push the horse over the reactivity threshold and cause a more ‘explosive’ response.

There are two general approaches we can take to reduce the chances of trigger stacking occurring and help our horse stay under threshold. The first is to actually reduce the size of each potential stressor so that, even stacked, they don’t cross the line. The other is to raise the threshold itself so that even when the stressors add up, they don’t quite cross the dotted line.

Making stressors smaller

Habituation

Habituation is the process by which repeated exposure to a stimulus stops producing a response. An example of this that many of us will be familiar with is the (inexplicable!) effect horse smell has on other people! When a non-horsey person gets in your unquestionably horse-tainted car, they make a face and show signs of distress. They tell you this is because the smell of horse is something they simply cannot stand! In effect, the smell of horse is a (very mild) source of stress for your friend. But you probably can’t even smell it… This is colloquially termed being ‘nose blind’ but it is the effect of long term exposure and is an example of habituation. With prolonged exposure, your non-horsey friend would stop smelling it too!

Counter-conditioning

At this stage you might jump in to point out that, actually, you never disliked the smell of horse in the first place! This is a common sentiment among people who love horses and it isn’t surprising… If the smell of horses reminds you of something you love, the smell is less likely to elicit a negative response in you. Forming a positive association between a stimulus and something nice is another way we can reduce the impact of individual stressors on horses. This process is termed counter-conditioning and involves changing the horse’s response to a stressor by transforming it from something that predicted or was an aversive itself to something that has become associated with something nice (such as food). Counter-conditioning is such a powerful tool in horse training that it can even be used to suppress and mask responses to pain. For this reason, we need to be very careful when we use it and make sure that we have eliminated physical causes of unwanted behaviours before we progress to using this technique.

Desensitisation

The final way we can reduce the impact of an individual stressor is desensitisation. Though this term is frequently used in the horse world, what people are normally referring to when they say ‘desensitisation’ is actually habituation. Desensitisation is a closely related idea – instead of repeated exposure to the same stimulus, desensitisation involves a gradual but systematic increase in the aversive stimulus or a step-by-step hierarchical exposure to elements of the ultimate stressor.

If you wanted to get your non-horsey friend used to the smell of horses, instead of exposing them to the complete olfactory experience of entering your horsey car, you could just let them experience a hint of the aroma at first. Once they are used to that, you can begin to up the ante with stronger equine scents. Over time and gradual exposure, your friend would become just as nose blind to the smell of horse as you are – and they would barely even realise that it had happened.

Similarly, if you have a horse that is afraid of clippers you can use gradually increasing exposure like this to desensitise them. Instead of holding the clippers immediately next to the horse and waiting for the horse to stop reacting, desensitisation would involve holding the clippers as far away from the horse as the horse needs to only show a mild response. You would then gradually bring the clippers closer if the horse remains relaxed at the previous distance. Eventually you would be able to bring the clippers right up to the horse without much reaction. For more severe stressors, this is a better approach than habituation as it avoids the potential for learned helplessness brought about by flooding.

Raising the reactivity threshold

I previously gave an example of trigger stacking that I think many people can relate to. We imagined what might happen if one morning, in a rush to get to work on time, we spilled some coffee on our clothes and had to get changed, forgot our phone, got stuck in traffic and eventually got to work late – only to snap at a well-meaning colleague who tries to ask for a small favour because this request is simply ‘the last straw’ for you. In this example, one way to try to prevent this outcome would have been to become accustomed to the inconvenience of spilling a coffee every morning and having to get changed… In other words, getting used to one of the stressors so that the stressor itself has a smaller impact.

In reality, it’s probably impossible to anticipate every little thing that could possibly go wrong and ‘get used to it’. And if not impossible, it’s certainly impractical! A different way we could try to reduce the chances that we would end up snapping at our colleague would be to practice staying calm under pressure or getting into the habit of thinking before we act. This is about increasing the actual threshold at which we react rather than trying to reduce the impact of individual stressors. In other words, we are trying to raise the dotted line on the graph.

The first way we can increase a horse’s tolerance to aversive stimuli and raise this dotted line is through the use of positive reinforcement to build an extensive bank of constructive experience with the horse. With positive reinforcement-based training, horses learn that there is always an ‘answer’ and can arrive at this answer without fear of consequences, in their own time. This encourages them to calmly think through problems and try to solve these instead of simply reacting.

In a stressful situation, this arms the horse with a new approach. Instead of panicking or spooking, the horse can take a moment to think and realise that they are not in any real danger. This also gives you a chance to step in and guide your horse to the ‘solution’.

In addition, having many positive reinforcement experiences with a handler builds a great deal of trust and confidence in the human, meaning that the horse is more likely to look to you for guidance and help in a situation that is stressful for them.

These effects, taken together, increase the horse’s tolerance to stressors and reduce the chance of the horse going over threshold and reacting explosively. Instead, the horse will stop and think about a possible solution to their predicament and turn to the handler for help and reassurance.

The other way we might be able to increase tolerance levels is through exposure to stressors. By regularly encountering stressors in a controlled setting, a horse’s reactivity threshold can slowly be pushed higher and higher. In addition, when they do react, they might be quicker to come back down to a base level. This is often a side-effect of systematic desensitisation and gentle habituation.

Even armed with all these techniques, we can never guarantee that a horse isn’t going to react to something. But putting time into working on this will also teach you what you can expect from your horse in a pressured situation – and teach your horse what they can expect from you! By building confidence and trust in each other, we can build a partnership that is much more resilient to the unpredictable environment around us and we can become better able to cope with anything that the world might have to throw at us!